lost in translation

thoughts on intimate communications

One of the biggest cultural shocks I experienced when I moved to the States after being raised in Colombia was accepting that the relationships I would build from that moment on would most likely be based in English. Quite an alien concept, as I had only seen english displays of affection in movies, never in real life. On top of it, words in Spanish carry some sort of passion while, in my brain, English is just descriptive. Today, four years later, I still have a hard time expressing myself with the right amount of intensity.

(English/Spanish) When you say I love you, do you mean te quiero or do you mean te amo?

It is no surprise that the question of the connection between love and language comes up as I interpret Spanish for a living. I am frequently told to use the most exact wording possible, when I know that there’s not an accurate formula for doing such thing. As Martin Pretchel explains on the Green Dreamer podcast1, languages contain ways of relating to and looking at the world, there are no simple equivalents to every word that you can indiscriminately exchange. And, more importantly, certain emotions themselves are culturally specific (Yurtaeva, E., & Charura, D, 2024)2.

(English/Spanish) I blame it on my short english vocabulary, though I know no combination of letters could teach you the feeling of awe when the cold water runs over your feet and you let the mosquitoes eat you up because, if you move, you might scare away the family of birds that are taking a shower in front of you. If I tried to, you’d call me crazy for deciding to take a dip in an unsupervised stream in the middle of the jungle. How did I ever expect you to love me when our instincts scream for us to do opposite things?

(Side note) Highlight of the podcast: “you speak your native language the same way an eagle cries”.

Although I can only speak from my point of view, I know this is an extensively shared experience. During a previous Substack meet-up, we were discussing our different backgrounds and how we have all learned to love in a language that’s different from the one our parents loved us in. Most of us agreed that loving in English feels easier, a little performative, less serious. Loving in our native languages carries a bigger burden and responsibility; it runs deeper, and every word carries a bigger weight. So what is it about love and words that is so troubling?

Katherine Caldwell-Harris3, explains that swearwords and expressions of love hit harder when expressed in the languages we learned through social interaction, which explains my soulless perception of English, which I learned in a classroom. However, that doesn’t respond to what happens if I experimentally learn to love from scratch in a second language.

Learning to love in english was a disruptive moment in my intimate communications journey. I was 23 and had a partner whose first (and only) tongue was English. Not only was it the first time I faced the challenge of communicating feelings, but I additionally had to do it through words that didn’t belong to me. I was borrowing a lexicon from social media, books, and movies, trying to fit them into the real world, trying to make them reflect my very-spanish feelings. After what ended up being a one-year rollercoaster, I had new skills in expressing needs and boundaries, both written and spoken, and in reading non-verbal cues from facial expressions that were completely foreign to my culture.

Sounds like a triumph, and it might be one, but having that experience abroad left a gap in my capacity to communicate in Spanish as an adult. Now I’m simultaneously relearning the art of having difficult conversations in Spanish and the art of attaching real meanings to the words I say and draw in English.

(Spanish/English) You cleaned my preschool wounds and high school tears, yet I can’t say I love you while looking into your eyes. Love in Spanish is still a foreign language.

This issue not only extends to my intimate communications but also to my professional development. My fancy words, learned in school, I know in Spanish, which make me feel more confident and smart; my practical words, learned from experience, I know in English, which scare me about one day performing my career back in Colombia. In one way or another, I feel like I’m lacking in both scenarios.

To add another layer, I’ve lately encountered people whose native languages do not match any of the ones I can speak. During those cases, we both meet at a middle point, which is usually english. These scenarios contain the biggest gaps because we’re both losing something in translation from our original languages. But even when that’s the case, we can both connect through the experience of feeling like outsiders. None of us feels the need to match the fluency level of the other because we know that language is a mere tool, and none of us trusts it completely, anyway.

(Tamil/Spanish) I translated my favorite Spanish love letters to Tamil in fear of losing their intensity if we met halfway. Nonsense intimacy as an antidote for English insipidness.

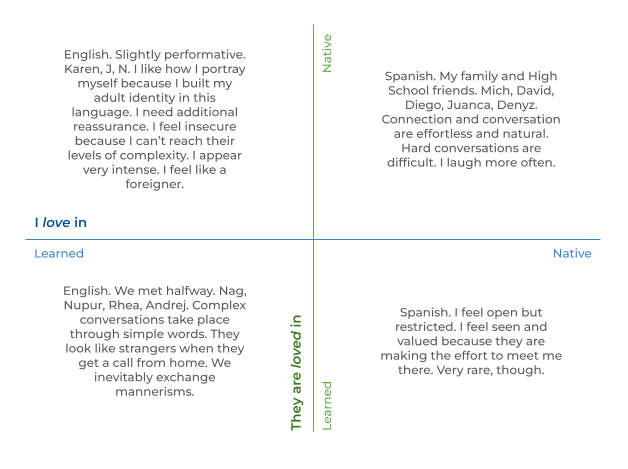

If I wanted to aggregate and summarize all my encounters, I’d say my experience of love is determined by the language in which the other person can receive love as follows:

My initial intention for this essay was to make it data storytelling post, correlating the level of connection with the type of language-relationship I had established, but when I tried to plot it, I discovered that I’ve been lucky enough to have loved and have been loved by people (and many other beings) on all of those spectrums. Turns out that what is determined by language is the type of experience, not necessarily its depth. A conclusion that caught me off guard and filled me with gratitude. So, actually, what is it about love that transcends words?

Oh, and (spoiler alert), Dewaele, J.-M., & Salomidou, L4 found that emotional communication does improve with time in a second language. I guess intimate communication is just another muscle.

This might feel open-ended. It’s by design, I’m still transitioning it. Maybe someday I’ll write a version that finishes the ideas. For now, these are additional untied thoughts:

✷ There are words that I only hear from my dad (i.e. catarro, troja). Will a part of my native language die the day he does?

✷ Culture is significantly transmitted through language, not through genes. What will that mean if I ever have kids who don’t learn my words?

✷ To what extent should written language be prioritized over conversations? Aren’t beautiful words meant to be spoken?

✷ Will my intercultural lovers and friends ever grasp the entire beauty of being South American?

✷ An important part of Caldwell-Harris’s paper on decision-making: “the stress of using a less proficient language could have diminished the cognitive resources needed for deliberative reasoning, thus pushing people to make gut, instinctive, or emotional responses”.

Also, I’m not trying to dismiss english as a profound language, I just haven’t had the chance to emotionally feel it that way yet.

AND on updates:

The Handmaiden!!!!! won’t say anything else because I don’t want to make spoilers.

Friends save lives, keep them close.

Is good enough good enough when there’s hope for extraordinary?

I got tickets to go to IAAC’s graduation!!!!!!!!! Can’t wait to be in the Mediterranean waters once again and to celebrate my favorite group of friends.

One of my dad’s favorite stories is the time a burglar tried to break into our country house through a fake window only to hit himself with the wall. I’m feeling that foolish lately. Maybe some doors do not open because there’s nothing behind them.

On How to do nothing by Jenny Odell: Online, our bodies are replaced by language, or become nothing more than images. What happens to our senses in this too-digital world?

Martín Pretchel: Relearning the languages of land, plants, and place. (2025) Green Dreamer. Spotify.com

Yurtaeva, E., & Charura, D. (2024). Comprehensive scoping review of research on intercultural love and romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 41(6), 1654-1676. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075241228791

Caldwell-Harris, C. L. (2015). Emotionality Differences Between a Native and Foreign Language: Implications for Everyday Life. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(3), 214-219. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414566268

Dewaele, J.-M., & Salomidou, L. (2017). Loving a partner in a Foreign Language. Journal of Pragmatics, 108, 116–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2016.12.009

I once dated a girl in Chinese; we both spoke English but when we started dating we switched to Mandarin completely and suddenly we were two different people, but still in the same bodies? It's hard to explain. Mandarin was her mother tongue and my mother's tongue and it felt so intimate expressing affection in the language I spoke with my loved ones as a child.

beautiful post !! I might write about language too sometime soon, if I can organize my thoughts on it….